Timeline

Timeless Challenges: Timeline of Migration, Policy, and the Environment in Classical History

Themes: Migration & Identity

The Odyssey, written by Homer in the 8th century BCE, is a classic tale of migration. Odysseus journeys across land and sea in search of his home.

Throughout his voyage, he encounters struggle and strangers, such as Circe and Polyphemus. Central to the Odyssey is the Greek concept of xenia, or the sacred obligation of hospitality that is backed by the god Zeus.

This moral expectation dictated that hosts must care for strangers in need, and guests must respect their hosts. In our modern world, marked by refugee crises, nationalism, and immigration issues, xenia is an ancient foundation for ethics.

Themes: Socioeconomic Inequality & Public Policy

In 594 BCE, the Athenian statesman Solon was granted extraordinary powers to reform his city, which was on the brink of collapse. His city was plagued with inequality as poor farmers were being enslaved for debts, and the political system heavily favored the wealthy elite.

Solon enacted sweeping reforms, canceling debts, banning debt slavery, and opening political participation to more classes based on income instead of birth.

Through his work, Solon laid the groundwork for more inclusive governance and economic justice. His legacy reverberates in today’s debates of wealth inequality and political engagement.

He demonstrates that democracy has always required difficult negotiations between freedom and fairness, and that rational reform is crucial to evolving as a nation.

Themes: Sustainability & Ethics

The Greek mathematician, Pythagoras (c. 570–495 BCE), most notably known today for his namesake theorem, also founded a philosophical/religious community that promoted ideals of vegetarianism, reincarnation, and a reverence for the harmony of nature.

While Pythagoras did hold some crazy beliefs, including a strange reverence for beans, his followers, known as Pythagoreans, believed in many interesting ideas. Some of these ideas were that all beings shared in the same cosmic order and that harming animals is morally wrong.

This early form of environmental consciousness placed limits on consumption and emphasized balance. Pythagoras’ environmentally conscious views parallel today’s discourse around the issues of climate change and sustainability.

Themes: Migration & Cultural Diffusion

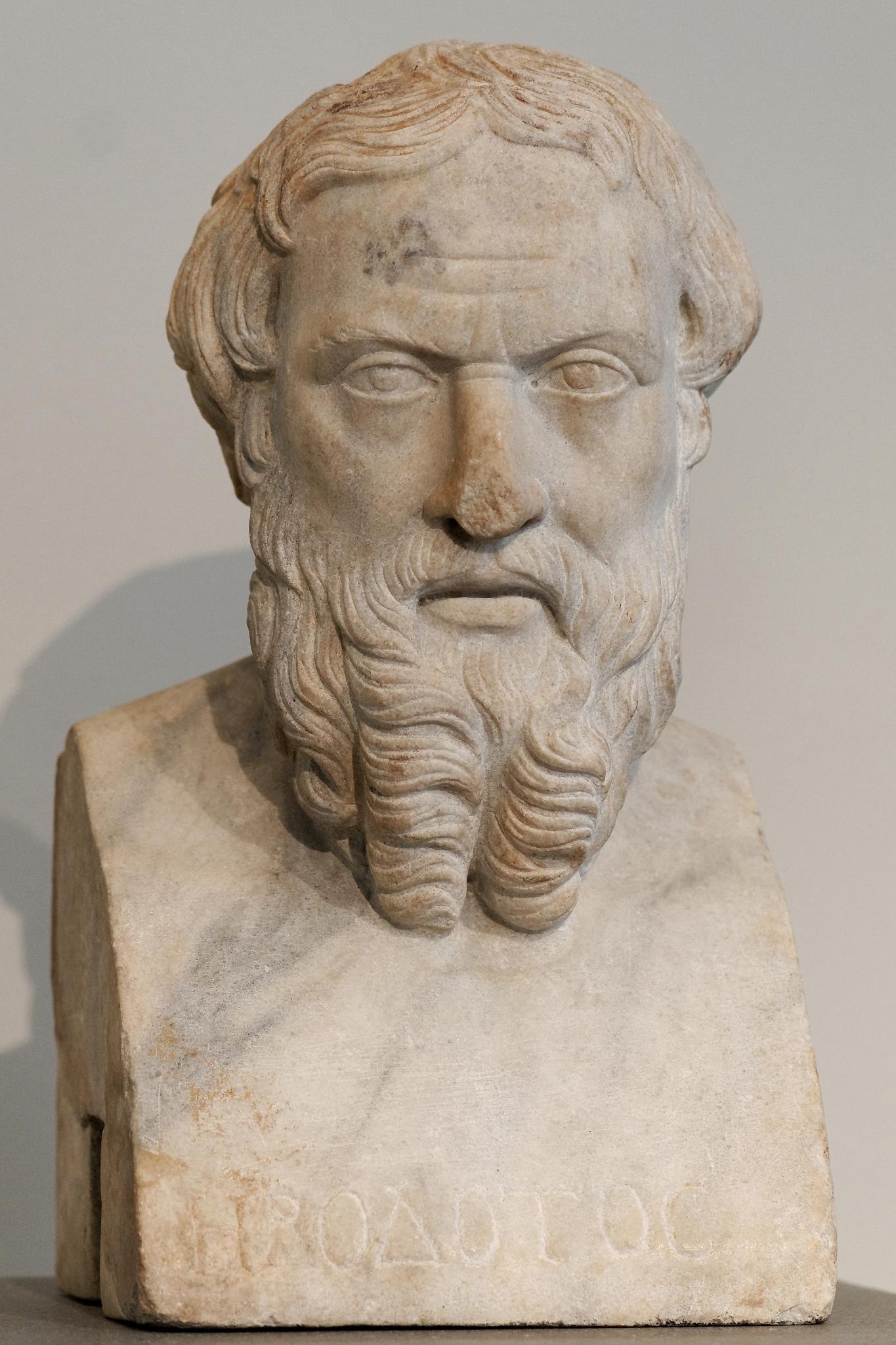

The Greek historian and geographer Herodotus of Halicarnassus (484–425 BCE), often hailed as the “father of history,” was fascinated by the movement of peoples, cultures, and ideas.

His Histories chronicle the Greco-Persian Wars, but also explains the customs, migrations, and myths of various peoples, including the Egyptians, Scythians, Persians, and more.

Through that work, Herodotus became one of the first authors to challenge the norm of the time, depicting the world as Greek versus Barbarian, instead approaching the world as a web of interconnected societies. For example, he depicted the positive qualities of Ethiopians, such as their truth-telling.

In today’s era of global migration and cultural mixture, Herodotus’ ideas remain surprisingly modern. His openness to other cultures and curiosity about human differences set an ancient precedent for tolerance and understanding of others.

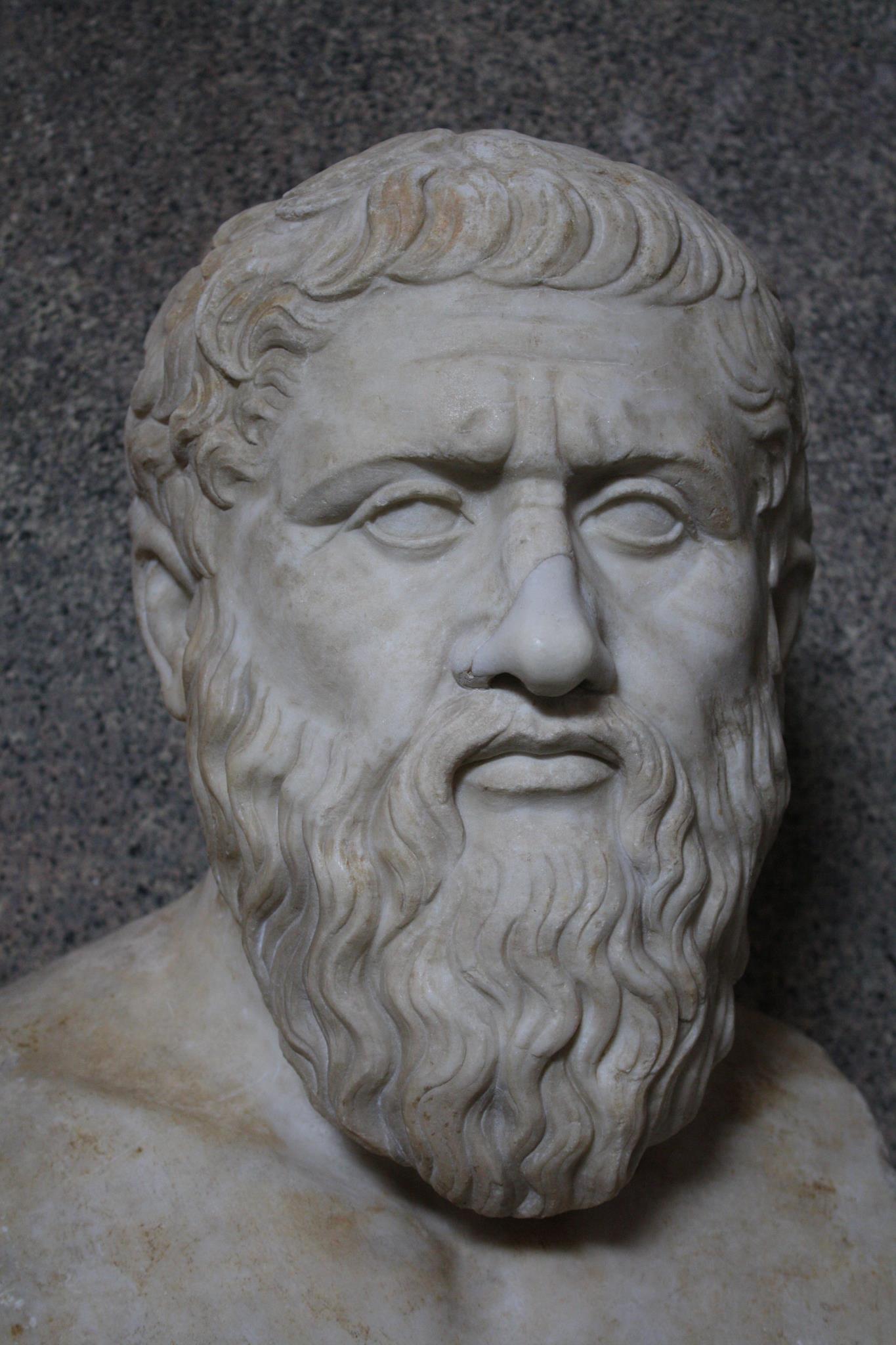

Themes: Justice & Public Policy

In his most famous work, The Republic, the Greek philosopher Plato created a provocative vision of a perfectly ordered city governed by philosopher-kings.

While his ideal state included rigid class structures and state censorship, it was meant to create a society with a foundation of harmony, justice, and the rational distribution of resources. Plato argued that society should be led by those most knowledgeable, not necessarily those most popular.

Today, debates over meritocracy, inequality, and technocracy echo Plato’s thought. Do experts have the right or duty to rule? Can justice be engineered? While these authoritarian leanings are troubling, the core question Plato introduced endures.

A just society does not reward power or wealth, but instead orders itself according to the good of all, whether that be through liberal democracy or other forms of government.

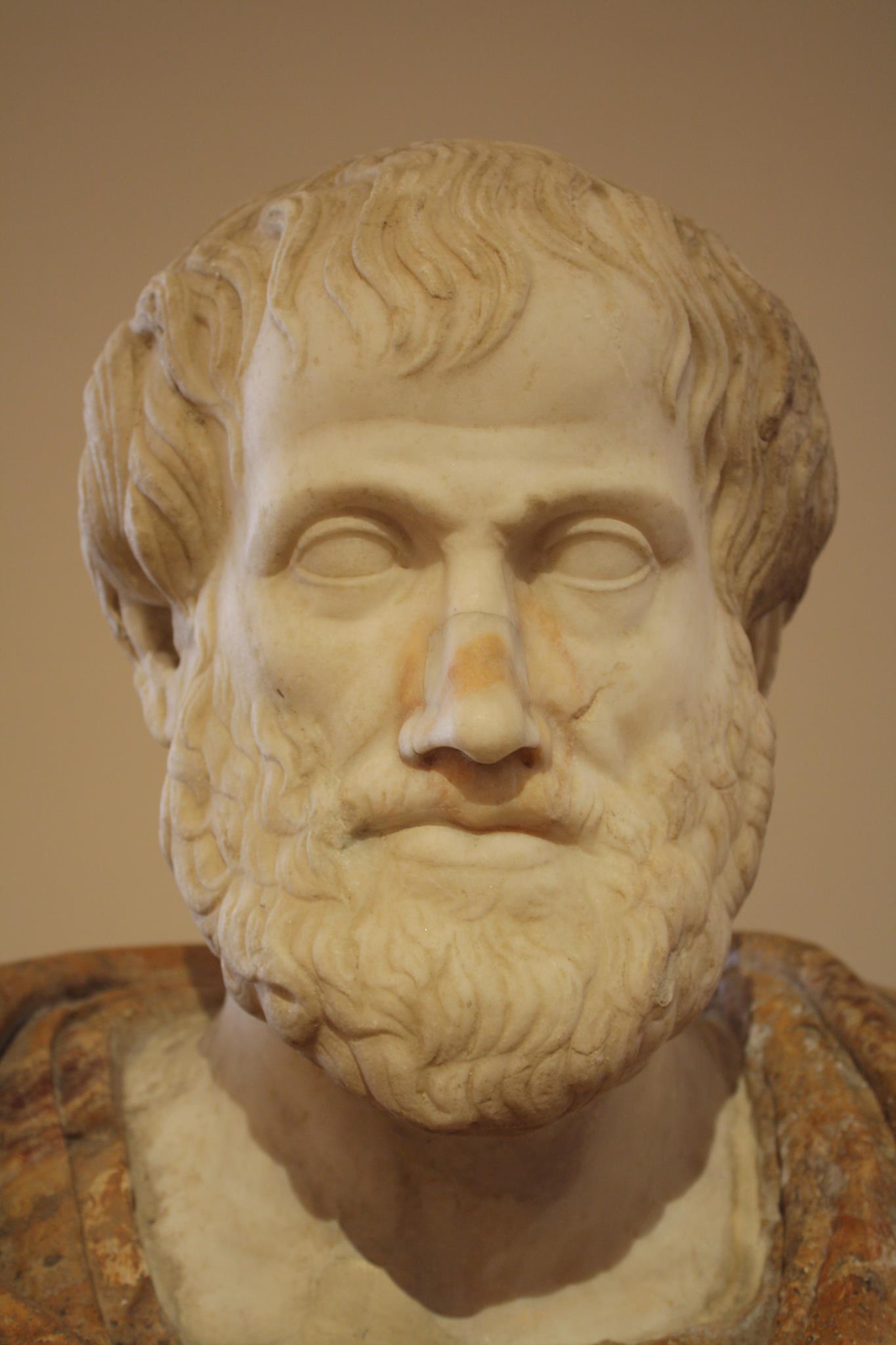

Themes: Virtue & Inequality

The Greek philosopher Aristotle (384–322 BCE) in his works, Politics and Nicomachean Ethics, explored how the structure of the city-state should promote eudaimonia, or a flourishing life.

For Aristotle, justice meant ensuring that political systems served the moral and material well-being of all. Aristotle was wary of extremes such as tyranny or mob rule, and promoted a mixed constitution as the best safeguard of justice.

Aristotle’s emphasis on virtue, responsibility, and the common good remains central to modern debates about citizenship, inequality, and public policy.

He reminds us that the purpose of government goes past order or efficiency and includes the cultivation of character, culture, and shared purpose.

Themes: Migration & Cultural Diffusion

Alexander the Great created one of the largest empires in history by the age of 30, but he also triggered massive displacement.

As his armies swept from Macedon through Asia and into India, cities were destroyed, populations uprooted, and entire regions transformed by forced migration. But his conquests also boosted cultural exchange.

New cities like Alexandria became commercial and learning hubs, and Greek ideas blended with Persian, Egyptian, and Indian traditions.

Alexander’s legacy highlights the drawbacks and benefits of global power with great disruption alongside connection. His story demonstrates how movement, whether through conquest or adaptation, has long shaped the world’s cultural and political landscapes.

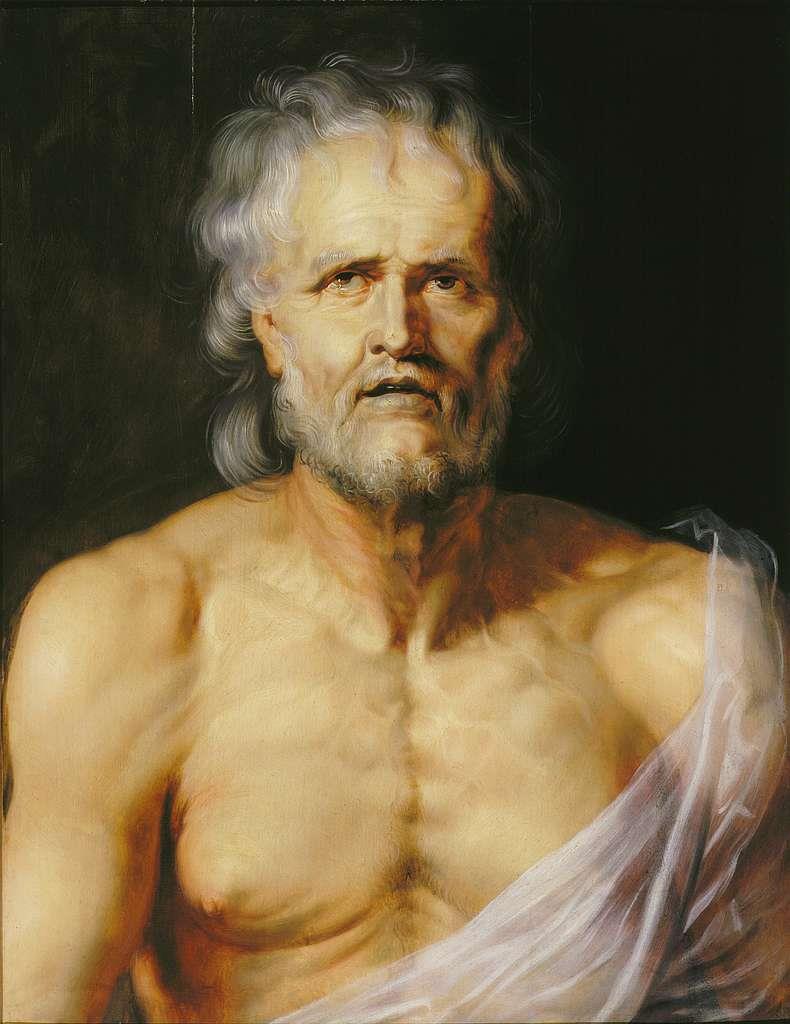

Themes: Temperance & Virtue

The Stoic school of philosophy, from Zeno of Citium to Marcus Aurelius, taught that true freedom lies in mastering one’s response to events beyond one’s control.

Epictetus, a former slave turned Stoic, argued that while we cannot control external circumstances like poverty, exile, and death, we can control our judgments, desires, and actions.

Marcus Aurelius, a Roman emperor, practiced these teachings throughout the hardships of imperial rule. He famously preferred a Stoic life of study and contemplation to his work as emperor. Today, as the climate of anxiety, political upheaval, and migration tests our resilience, Stoicism offers tools for keeping ourselves strong.

Focus on what you can change, accept what you cannot, and act with integrity regardless. In a world plagued with uncertainty, Stoic virtues may be more important than ever.

Themes: Technology & Sustainability

The Romans were masters of construction, building aqueducts, roads, sewers, and public baths whose ruins can still be found today. Roman infrastructure was a symbol of order, wealth, and power.

Their technological prowess and wealth were demonstrated through over 50,000 miles of paved roads, bridges like the Pont du Gard, and aqueducts that carried millions of gallons of water daily to cities such as Rome and Constantinople.

They pioneered the use of opus caementicium (Roman concrete), which allowed them to construct beautiful buildings and projects like the Pantheon’s dome and the multi-level Cloaca Maxima, one of the world’s earliest sewage systems. These projects also reinforced imperial power as public baths like the baths of Caracalla showcased Rome’s ability to provide leisure and cleanliness to its citizens.

However, not all Romans benefited equally. Elites owned private fountains, while slums lacked sanitation. Today’s infrastructure debates on climate change, green energy, and equitable development mirror Rome’s dilemmas. How do we build for everyone, not just the powerful? Can we create systems that endure without harming the planet?

Theme: Security, Governance & Public Policy

When Augustus rose to power in 27 BCE, he established an imperial system that centralized the power of Rome under his control.

Through political savvy and propaganda such as coins bearing his image, titles such as princeps (first citizen), and monuments like the Ara Pacis, Augustus dismantled the Roman Republic and entrenched his control. His regime offered stability after years of civil war, but at the cost of democratic institutions. The Senate remained, but with diminished influence as the legions swore loyalty to him personally.

Augustus’s transformation of Rome into an empire reflects a recurring theme in history: power consolidated in the name of peace.

Today, in moments of crisis, whether it be war, pandemic, or political unrest, governments may similarly expand authority while promising security or restoration. Augustus’s takeover of Rome reminds us of how easily republics can shift toward authoritarianism.

Themes: Moral Responsibility & Wealth Inequality

Lucius Annaeus Seneca, advisor to the Emperor Nero and a leading Stoic philosopher, lived a life of contradiction.

As a member of the imperial court, he accumulated vast wealth and navigated imperial politics. Yet, his essays on anger, mercy, and the shortness of life reflect a deep concern with the moral costs of excess and the fragility of fortune. Seneca warned against greed and reminded readers that no one who has enough is poor.

In today’s age of billionaire philanthropy, wealth inequality, and moral posturing, Seneca’s life and writings challenge us to examine the dissonant contrast between Stoic values and lifestyle and to ask,

“What does it mean to live well, not just live richly?”

Themes: Migration & Politics

The Western Roman Empire officially fell in 476 CE, but its decline unfolded over decades of military decline, political fragmentation, and economic strain.

As Rome weakened, waves of migrant groups such as the Goths, Vandals, and Huns crossed into its borders. Some came fleeing violence, while others sought opportunity. These migrations included invasions, resettlements, alliances, and cultural exchanges that reshaped the continent.

Known as the “Migration Period,” the years between 300 and 700 CE were marked by upheaval and transformation as old systems broke down and new political and cultural groups emerged across Europe.

In today’s world, where mass displacement due to war, climate change, and political instability is reshaping borders and identities, the fall of Rome is both a warning and a lesson. Societies under stress can crumble, but they can also adapt, rebuild, and evolve.